The internet is a pretty rough and tumble place to hang out. It's not even that there are so many jerks out there, it's just that all of them can reach you at once. Luckily you have the power to shut them down.

This installment focuses on blocking IP addresses that are doing things they shouldn't. It's the lastest in a series of posts on

- Setting up a webserver

- Setting up a domain name

- Setting up some security

- Keeping a webserver healthy

Block an IP address

The most straightforward way to block and IP address is in the firewall. It is the tool build specifically for this.

To block the address 101.101.101.101, run from the command line

sudo ufw insert 1 deny from 101.101.101.101

This instructs ufw (the Uncomplicated FireWall) to insert a rule at the the top of the list (position 1) to deny all incoming traffic from the address. After running this, no restart of the firewall is needed. The rule is active. (ufw docs

The position 1 is important because in ufw, the first rule that matches

is applied. If there was a rule to allow all addresses that started

with 101. and that rule came before the deny rule, then the deny

rule would never be reached.

While it's possible to block specific ports, or even to block an IP address from seeing particular pages, complex rules and conditions get difficult to analyze very quickly, and can lead to cases where there are loopholes. Use fancy rule combinations sparingly.

Parse logs

In their raw form access logs are technically human-readable, but they are a lot. I found it really useful to do a little parsing to pull out the bits I'm interested in. (I'm working with the default nginx log format, so adjust this according to your own.)

I wrote a script to take advantage of the repeatable structure of these logs to dissect them into their parts. It uses tricks like splitting the log based on brackets and spaces. It productes a pandas dataframe with columns containing the IP address, requested URI, HTTP status code, and every component of the date and time.

If you use exactly the same setup and log format as I do you might be able to get away with using this code right out of the box. More likely you'll have to (or want to) adjust it a bit for your own circumstances. Make it your own!

This better organized version of the log can be used to generate a list of pages that were queried, a list of IP addresses that visited the site, or even just a chronological list of every access attempt.

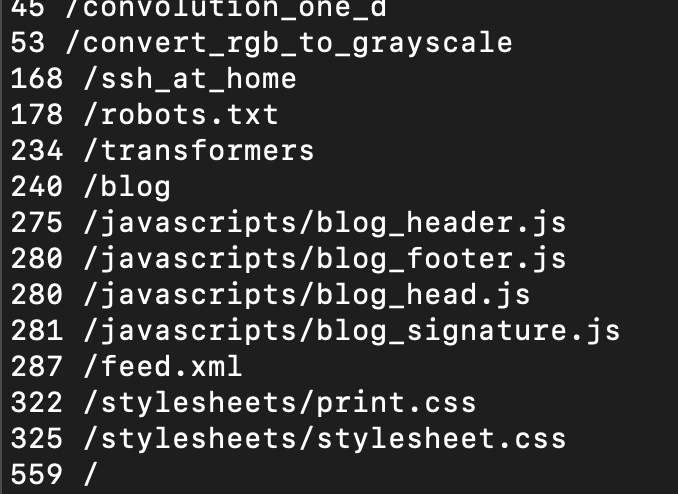

Here's a pages.py script that shows how many times pages were hit in a given day, for example

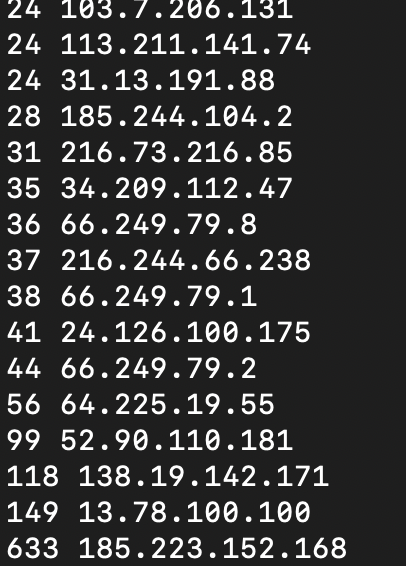

Here's a ips.py script that shows how many times a particular IP address visited that day

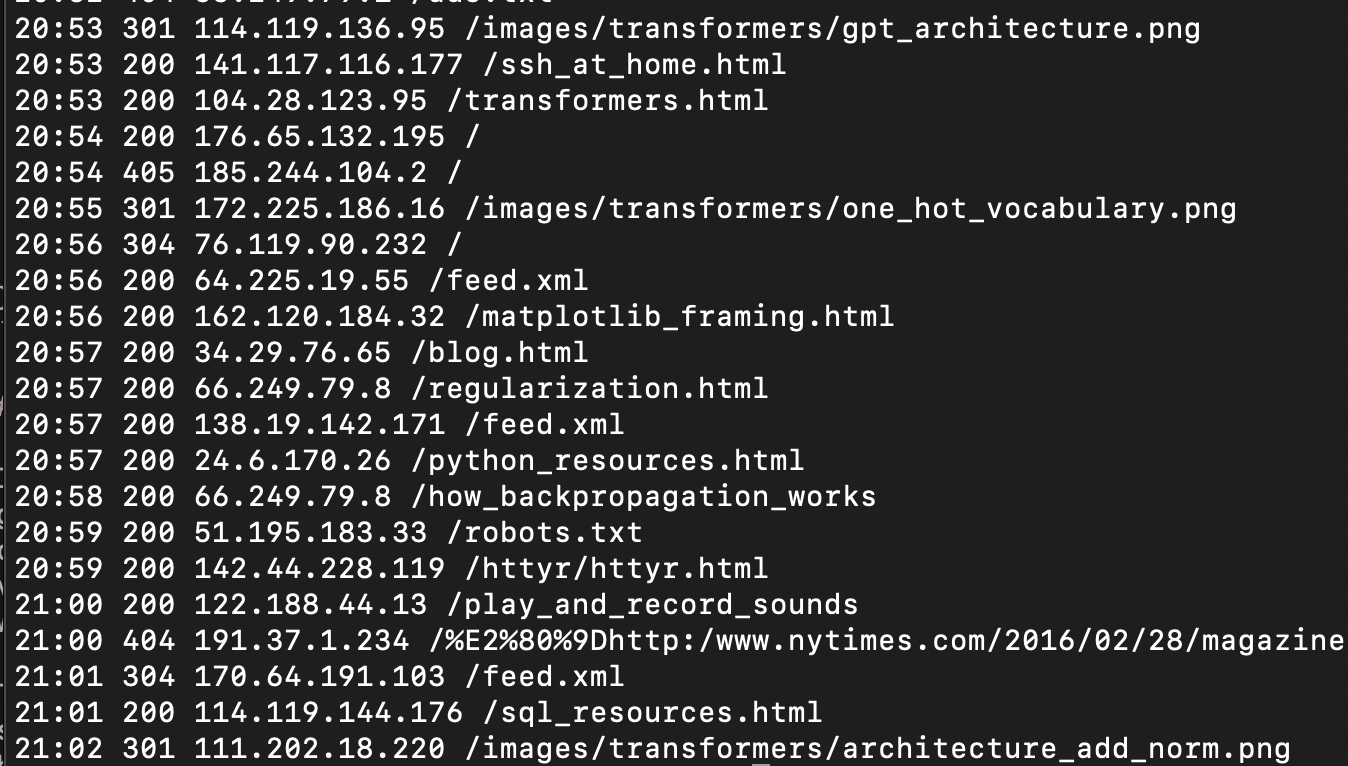

Here's a history.py script that just repeats the access logs directly, but in a stripped down format that's easier to read.

Browsing the logs

At first glance these logs are just an unbroken wall of text, but after spending a couple of minutes with them, oddities emerge.

Looking at the IP address access count, why is there one address that accessed the website 633 times? That's more than four times the next most frequent. What was happening there? Surely that can't be legit, can it?

Looking at the access history, why was someone trying to find a 2016 New York Times article on this website? (The funny characters that come before are a utf-8 encoding of a unicode right double quotation mark.) That looks like someone was really flailing.

Looking at the pages viewed, once you get past the stylesheets,

javascripts, feed.xml., and robots.txt, there is the top-level blog,

a popular post about transformers which I put a ton of effort into, and

then ssh_at_home, a hastily-written set of notes about setting

up an ssh server for personal use. Why is that one so regularly visited?

The longer you look, the more questions arise. Some of the most interesting patterns come from people doing mischief.

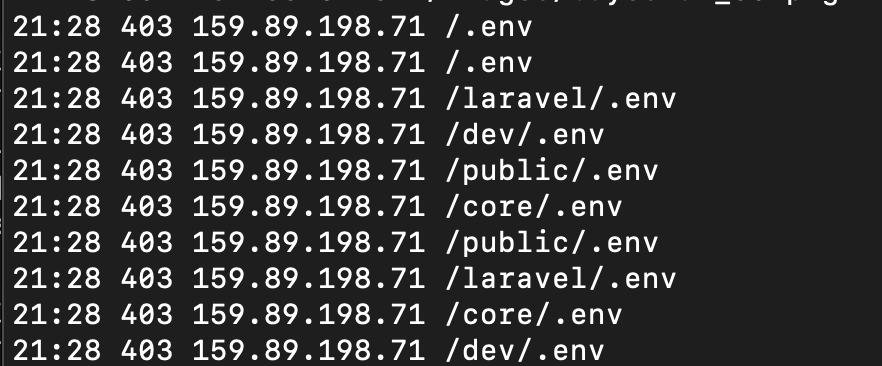

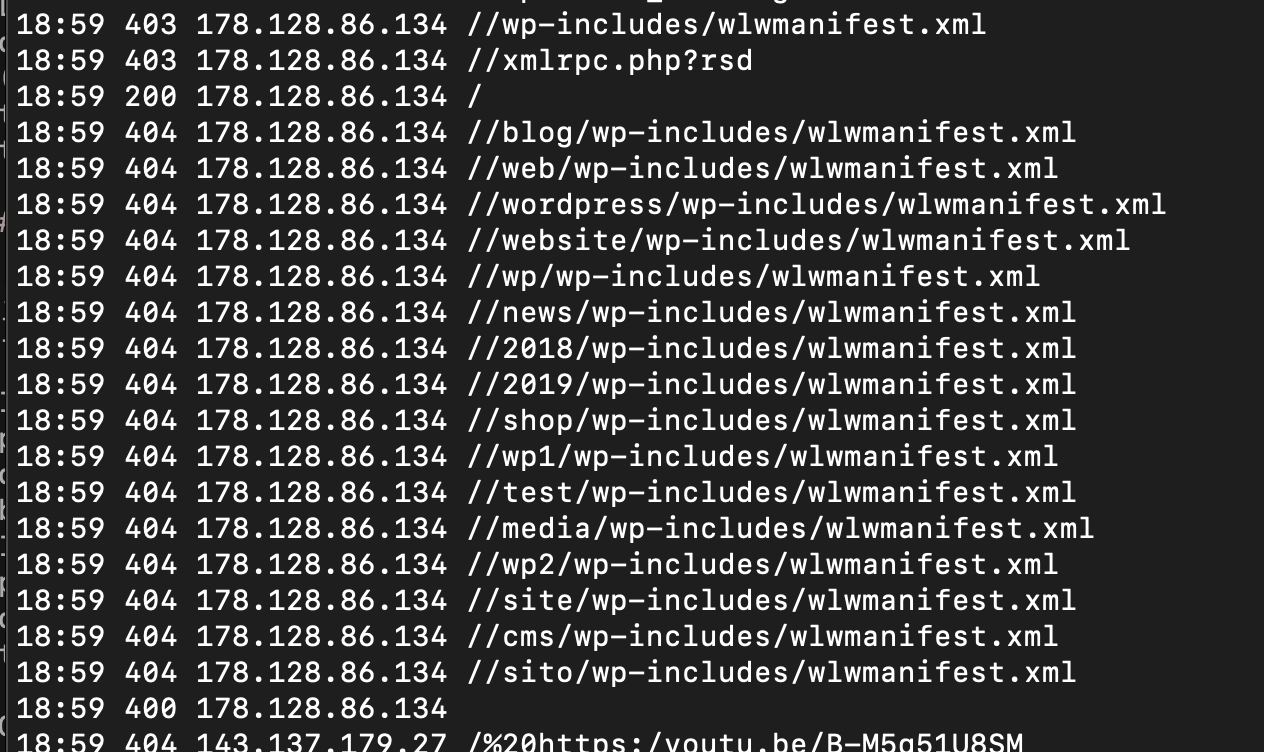

Bad behavior #1: Scanning for secrets

Here, a single IP address quickly tries to access a handful of variations

on a .env file, which is a common place to store access tokens

and other credentials. There is no good reason to be doing this, unless

you are doing it to yourself, proactively scanning for vulnerabilities

in order to fix them.

In my judgment this is a one-strike-and-you're out behavior. This IP address will get added to my block list. Luckily we already blocked access to all dot-files in the nginx server block during initial setup. That's why these are resulting in a 403 status code (access denied) rather than a 404 (not found). But if someone is doing this they may be looking for other ways into your system. Why not just block them at the firewall?

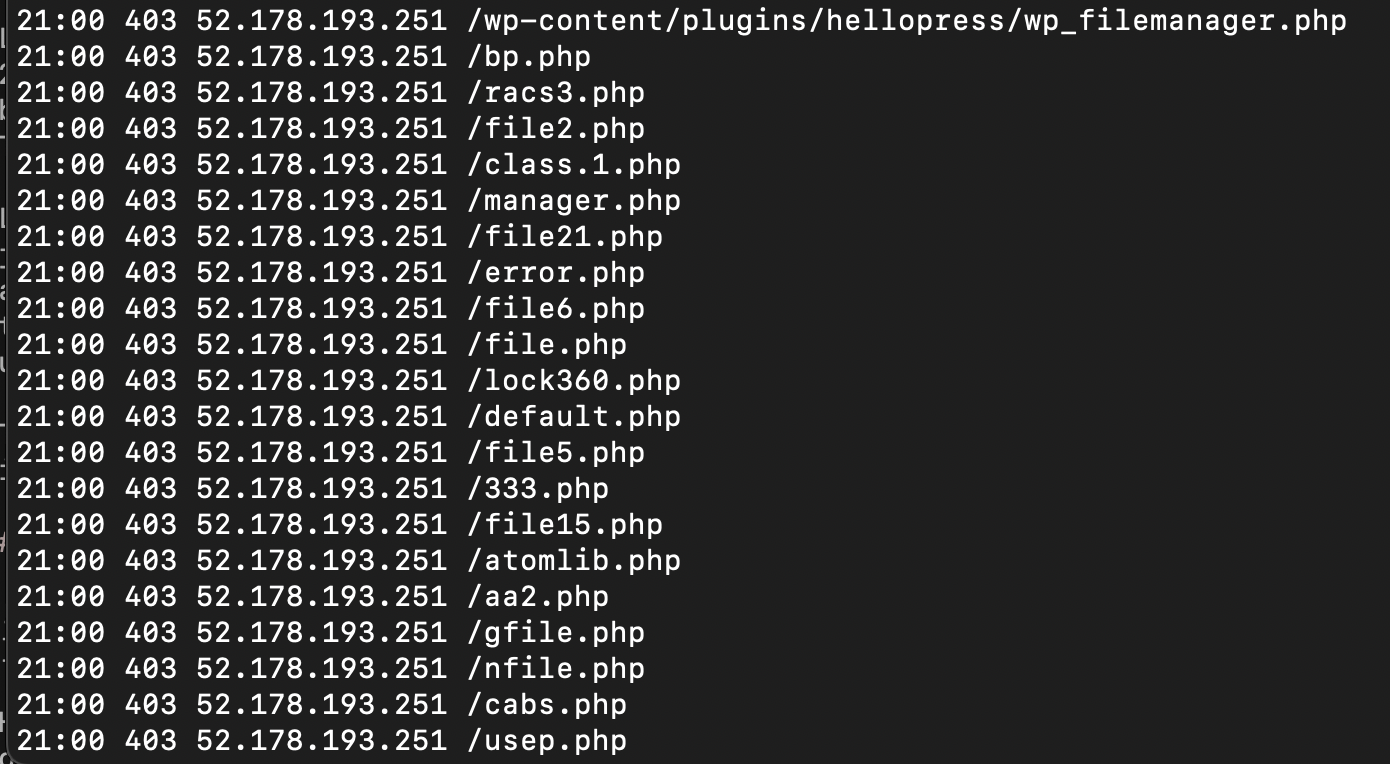

Bad behavior #2: Fishing for files

In this segment, a single IP address is trying to find a php file, and they appear to be randomly casting about. These files don't exist on my webserver and never have. This requestor appears to be shooting in the dark for files that they do not have a link to. I don't know why, but I don't like it. I have all php files blocked in my server block, but still this behavior shows someone doing something other than browsing my website, which leads me not to trust them. For me, this is a blockable offense.

Other file fishing I see often is for WordPress-related files.

I also get requests trying to access links from my pages, as if they were

hosted on my server, such as

/%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20https:/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convolution.

The %20 is URL encoding for a space character. I also don't know why

there are 12 spaces in front of the URL. It looks like sloppy automated

parsing of a bot accessing links that were extracted from my html files.

I don't know what benign purpose this could serve. I'm content to

block these as well.

With the history browser there is a --status argument that lets you

quickly see just the 404's and 403's and 400's (bad request error)

and helps the file fishing to pop out.

uv run history.py --status 404

Bad behavior #3: Rapid-fire requests

Sometimes an IP address will make a lot of requests in quick succession. Most of the time this is a mild annoyance, but when taken to an extreme it floods the server, preventing any other requests from getting through. It denies everyone else service, earning the name Denial of Service (DOS), and whether done maliciously or through negligence, the effect on your website is the same.

A lot of back-to-back requests is almost always a hallmark of automated scraping. It's a personal judgment call, how much you want to support this. The intended audience for my website is individuals, rather than AI-training companies or even search engines, so I'm comfortable making life uncomfortable for bulk-scrapers. There are two ways to do this.

The first is to set up rate limiting. One rate limiting mechanism is a

polite request in the robots.txt file to limit requests to, say,

one every 5 seconds.

User-agent: * Crawl-delay: 5

Unfortunately, manners are in short supply on the internets, and most crawlers and scrapers, including Google, ignores this directive. We can resort to more draconian measures and use nginx to implement per-IP rate limiting on the webserver.

This is done with a modification to the server block, as here and here

limit_req_zone $binary_remote_addr zone=one:1m rate=1r/s;

server { limit_req zone=one burst=10 nodelay; limit_req_status 429; }

These lines create a "zone", a 1MB history of IP addresses that have made requests. On average, they should be making no more than 1 request per second. It allows for "bursts" of 10 additional requests, serving them immediately with no delay, but anything in excess of that which violates the rate limit will receive a HTTP status code of 429 (too many requests).

There are a lot of possible variations to this, but this is the basic pattern. For a deep dive, check out the nginx docs.

And of course it's always possible to block IP addresses who try to pull this.

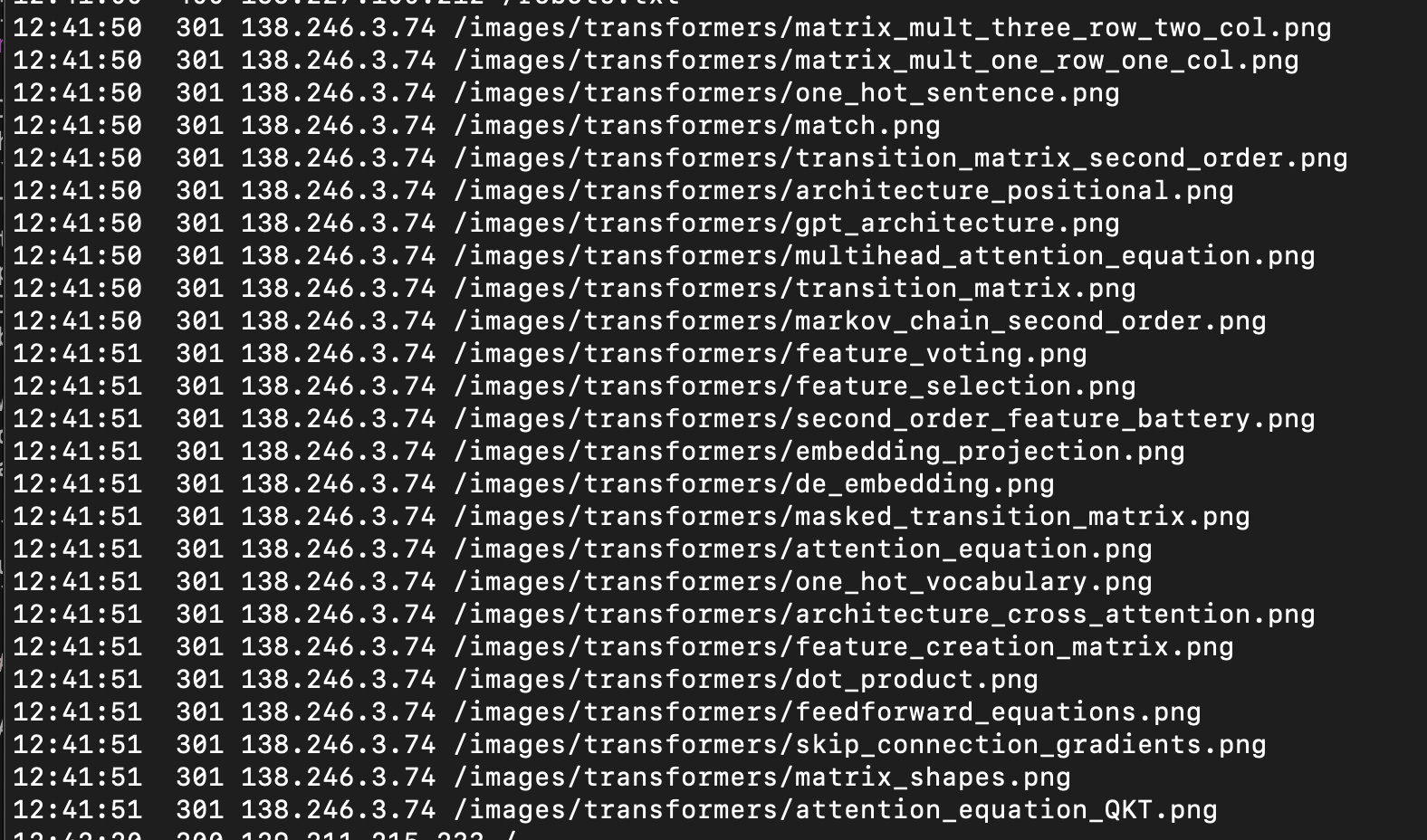

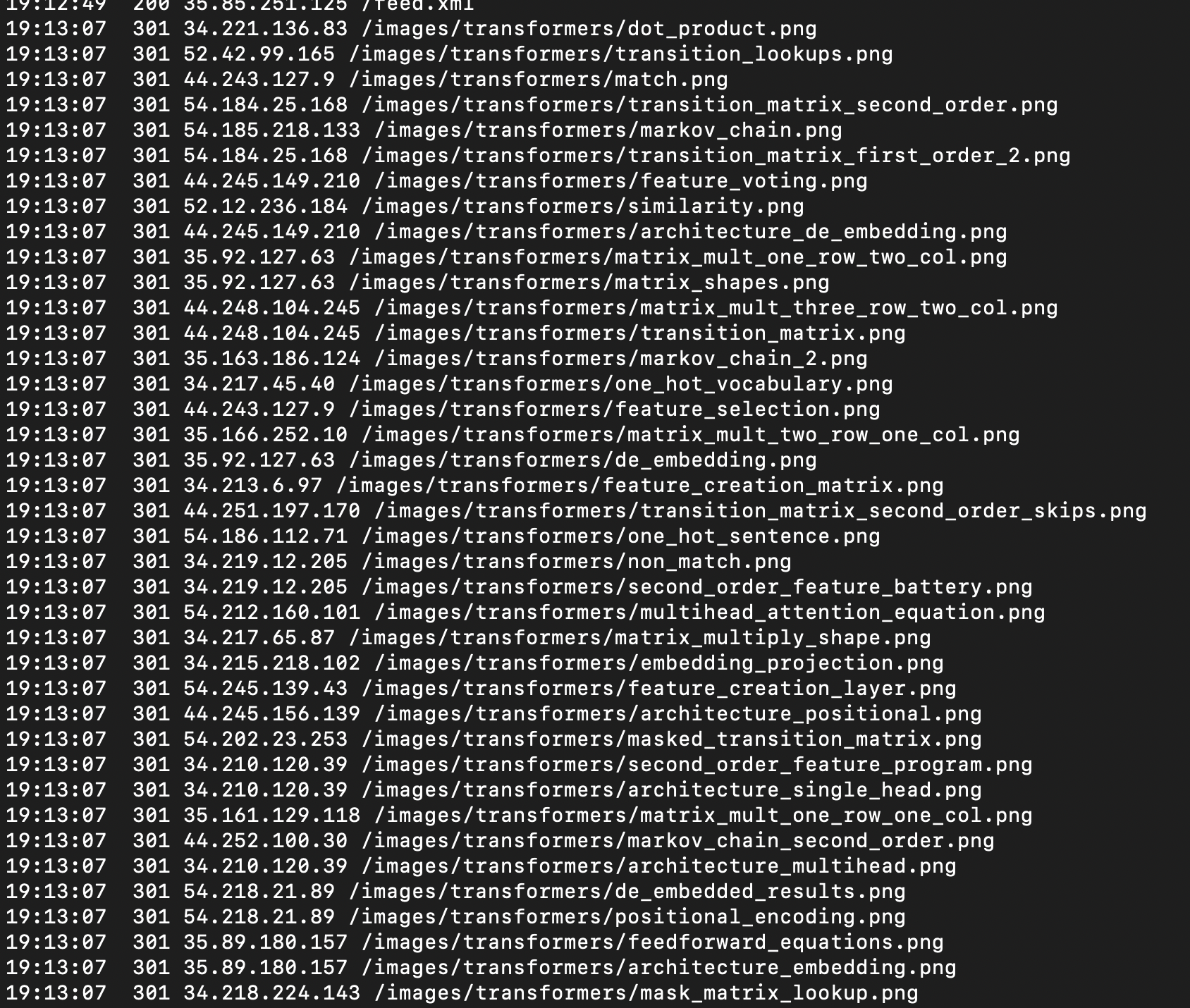

Bad behavior #4: Trying to hide rapid-fire requests

Given how easy it was to rate limit a single IP address it should come as no surprise that enterprising webscrapers have found a cheat. If they split their requests across a whole bunch of IP addresses, then rate limiting on a single address doesn't slow them down.

This even hides behing a respectable-sounding techy name: rotating proxies. But underneath it's just a way to get around website admins' express desire that these jerks not do this thing.

Detecting this is trickier. In the example above, it's clear to a human eye, that the requests are part of a coordinated scraping operation. They all occur within one second. They are all requesting a .png within the same directory. The IP addresses, while containing just a few repeats, fall into a handful of clusters. But writing rules for automating this is hard. Every rule you can come up with will probably miss some coordinated scraping, or deny some legitimate traffic, or both. Even machine learning methods, which can take multiple factors into account, may not be able to do this cleanly.

Of course dangling a tricky problem like this in front of nerd is like waving a red cape in front of an angry bull. I'll probably come back to deeper treatment of it later. For now the only strategy I can recommend is manually blocking every single IP address involved.

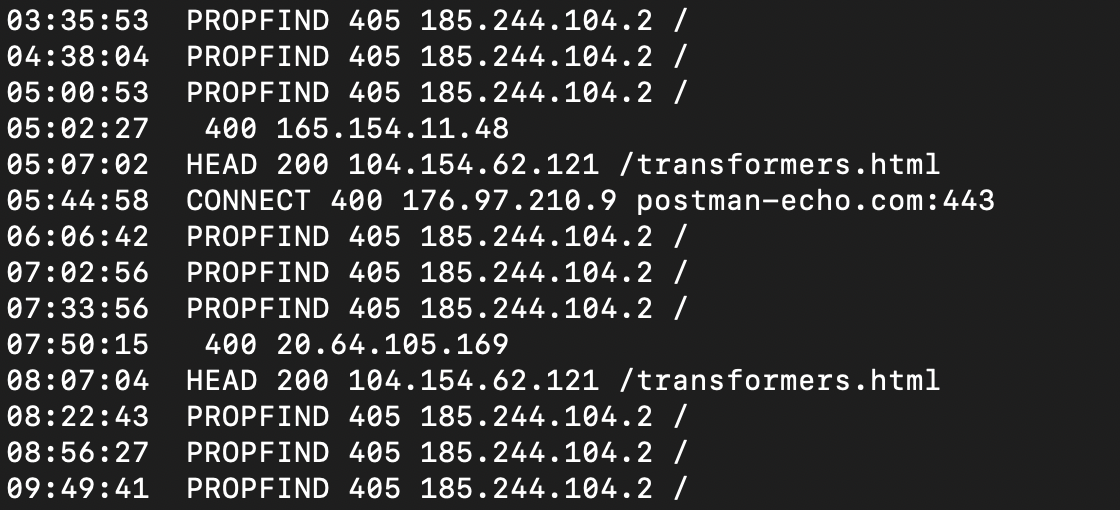

Bad behavior #5: Attempting unsupported actions

There are just a handful of things you can do over HTTP. GET and POST are

the most common, and HEAD comes up sometimes (get info about a page

without downloading it) but there are others that almost never come up in

the normal course of events. PROPFIND is a way to gather information about

all the available files on a server. It's easy to imagine how convenient that

would be for a scraper. CONNECT sets up an open pipe for data to flow to

and from a server. Nothing I would want to enable for a client I don't know

and trust.

For my little static website in particular, the only valid actions are

GET and HEAD. There is nothing to PUT or POST and everything

else I have no intention of allowing. I've never offered these actions

for any purpose, and it's very likely that any requests that contain them

are trying to get access to data and functionality they shouldn't have.

Block-worthy behavior in my book.

Blocking revisited

From the list above, there are a lot of offenses that can get an IP address blocked, and a lot of IP addresses that commit them. It would be possible to manually update the firewall rules for each one at the command line by running something like this

sudo ufw insert 1 deny from 101.101.101.101

for every blocked address, but after my blocklist passed several dozen addresses it started to feel tedious. Updating the list became difficult after the list passed 100 addresses. When adding new addresses manually I didn't want to duplicate the ones that were already there, so I sorted them and added new ones into the list where they belong. Duplicates were readily apparent. But after the list grew to fill several screens lengths, updating became slow.

To streamline, I created a blocklist_additions.txt with every IP address I wanted to disallow. Then a small Python script update_firewall.py was all I needed to automatically run the list.

sudo python3 update_firewall.py

This lets me browse through the logs and manually add problematic

IP addresses to the file blocklist_additions.txt on the server.

Then I can update the firewall with the latest changes.

Some of these behavior violations should be straightforward to detect programmatically. Automating firewall updates will be an adventure for another day.

October 6, 2025